BioScan

Monitoring Wetland Invertebrates - the little things that run the marshes

RoAM volunteers are active in running a monthly Malaise trap which provides specimens for DNA analysis in a large national project called BioScan. Locally, there are benefits in providing data for many small and overlooked invertebrate species which are not usually recorded in other ways. This is complementary to RoAM’s other invertebrate monitoring activities based on photographic records, sweep netting, field observations and moth trapping.

The Bioscan Project

BioScan Project is a national scientific project led by the Wellcome Sanger Institute, based near Cambridge. Natural England is the formal partner in BioScan for the Shapwick Heath NNR. Following a pilot year involving ten sites (including Shapwick), the project has expanded to include around 100 sites across Britain. The aim is to record and identify using DNA barcoding around a million specimens from those 100 sites over a ten-year period.

The sampling mainly targets flying invertebrates. Specimens are collected using a Malaise trap, which is a tent-like flight interception trap. Sites run the trap for 24-hours every month throughout the year. Specimens are placed into wells containing ethanol in a 96-well plate and then sent to Sanger for DNA barcode analysis. This process extracts DNA from the liquid in the cell and is non-destructive so that specimens can be examined later if necessary. The data is publicly available on the Sanger website.

BioScan at Shapwick

Initially we ran two traps, one alongside a reed bed, but from March 2022 we have been operating a single trap in birch woodland at Canada Farm. RoAM volunteers set the trap and collect the catch every month, usually for a 24-hour period. About every three months we meet for a plating session. We place each animal in a separate cell and record an identification. This is usually at a very high taxanomic level, just whether it is a fly (Diptera), bug (Hemiptera), wasp (Hymenoptera) etc. About every year we send a package off to the Sanger Institute.

The most common animals in the catches

At the time of writing (Sep 2025) we have results back from Shapwick Heath from May 2021 through to Jan 2025 comprising 9,362 identified specimens. Of these, 51% are flies (Diptera), 31% are bugs (Hemiptera), 13% are from the largest group of springtails (Entomobryomorpha) and 11% are wasps, ants or bees (Hymenoptera). There are smaller numbers of beetles, spiders, moths, bark lice, harvestmen etc.

The most common fly

The most common family of flies is the Chironomidae, the non-biting midges. With 19% of all records, almost one in five animals caught is a midge. The most common species is Limnophyes minimus, with 457 records which is 5% of the total. This is a very common midge found in all six biogeographical regions of the world. The larvae are detritivores and are thought to play a very important role in ecosystems in consuming plant litter and recycling nutrients. Most of our Malaise trap records are from the winter and early spring (Nov-Mar) indicating the peak period when adults are on the wing.

The most common bugs

As the trap is located in birch woodland, it is not surprising that we get large numbers of the Birch Catkin Bug Kleidocerys resedae. This plant-sucking bug produces several generations per year, with adults present in the trap throughout the year.

The second and third most common bugs are two species of the genus Linnavuoriana, family Cicadellidae. L. decempunctata and L. sexmaculata are similar looking leafhoppers, differing mainly in the number and arrangement of dark spots on the vertex and pronotum. In our catches the two species are present almost solely in November and December. This is probably the time when the adults are on the wing, moving from feeding in the trees in the summer to their wintering roosts among evergreen plants.

The most common wasp

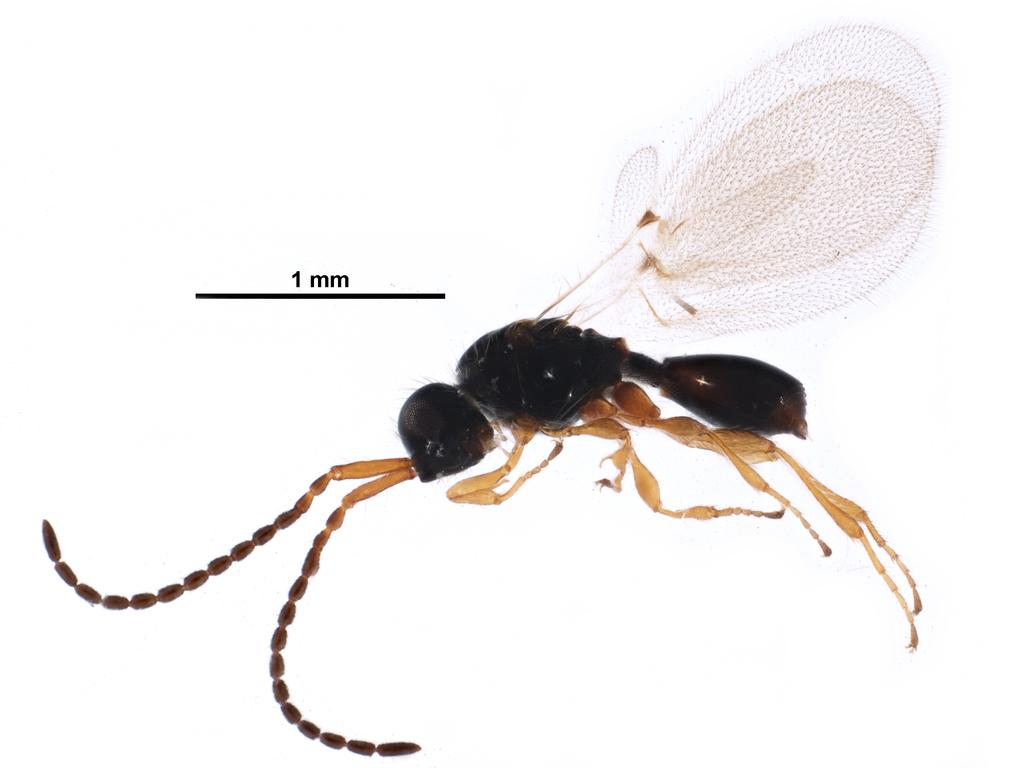

The most common wasp families are the ichneumons (family Ichneumonidae) and the braconid wasps (family Braconidae), but the records contain many different species with small numbers for each species. The species with the highest number of records comes from the third-ranked family, the Diapriidae, and it is Basalys formicarium. There are 27 British species of the genus Basalys and they are all small at around 1-2mm.

In the BioScan catch they are instantly recognisable as the wings are covered in long hairs obscuring the usual pattern of veins. As for the vast majority of wasps, they are parasitic but the hosts for the British species are in most cases unknown. Occurrence in our trap is primarily in May-June and again in August-October.

In conclusion

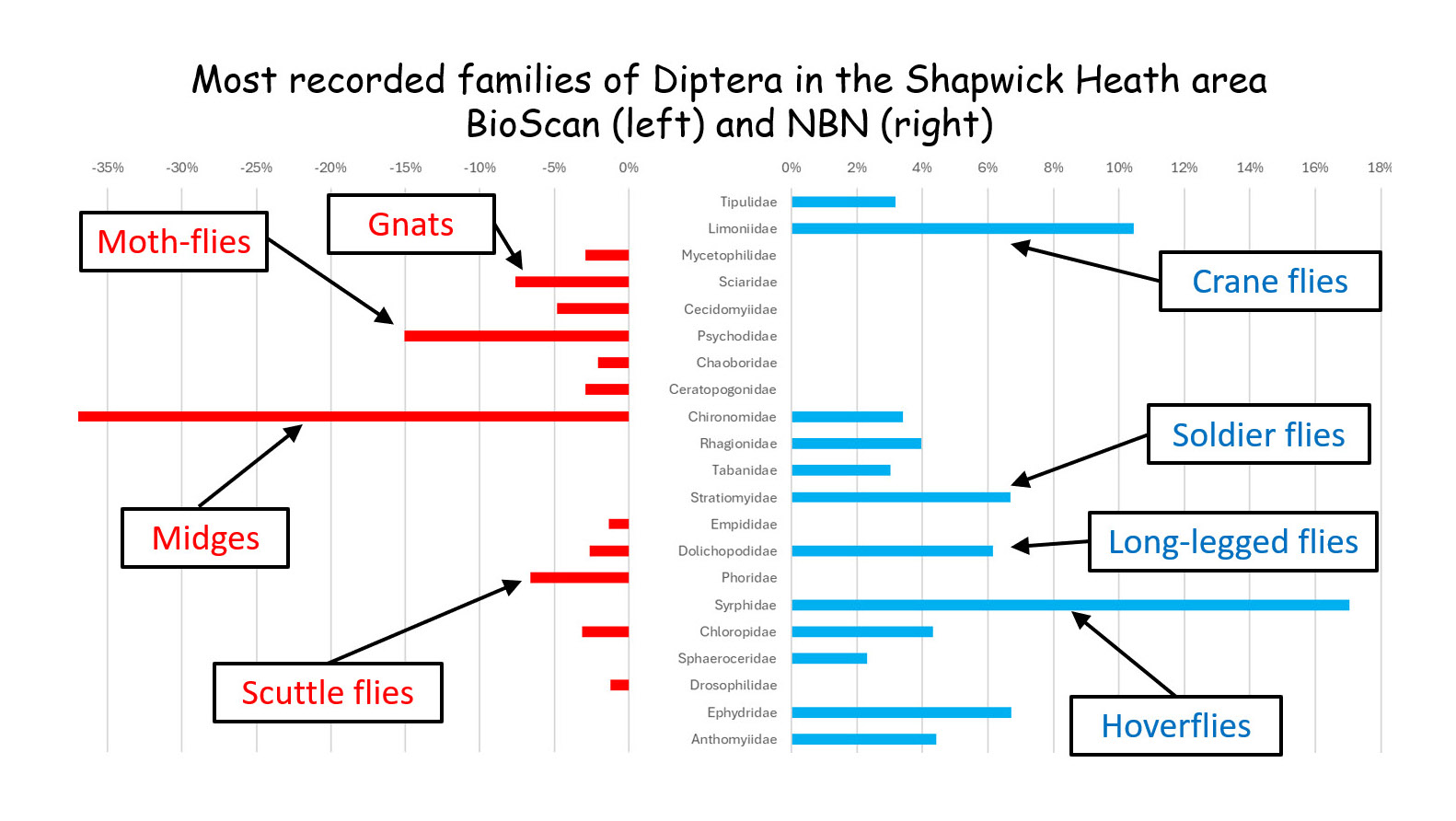

In general, the animals caught in the Malaise trap for BioScan are mainly small, unnoticeable creatures which are seldom recorded by other methods. But they are crucial to the functioning and good health of the ecosystem. For example, the top six families of flies are various families of midges and gnats plus the moth flies and scuttle flies. By comparison we can look at the NBN records for the Shapwick Heath area. They are mainly derived from photographs or from collection by sweep netting. And tend to focus on the bigger, more easily identifiable species, e.g. hoverflies, soldier flies, crane flies, and long-legged flies.

Thus, BioScan provides a wealth of data which is complementary to most other recording methods. And tells us a lot about “the little things that run the marshes”.

Getting involved

RoAM welcomes volunteers to work on the BioScan project. Examining a catch under the microscope and sorting the catch into cells is fascinating. You will have the chance to see in great detail amazing creatures that you do not usually see by any other way, and to learn about the little things that contribute to the wetland ecosystems. Please contact RoAM if you would like to get involved.